Badly thought-out list of goods? – Gufic

The case: The Indian company Gufic Biosciences Ltd, which sells frankincense tablets in Germany, as well as in other countries, wanted to avoid using a badly thought-out list of goods for its product brand. The tablets contain, as an active ingredient, resin from the frankincense plant Boswellia serrata, and they are labelled under the EU trade mark

![]()

Gufic Biosciences had registered the mark for a wide range of goods, including ‘incense’ and ‘cosmetics’ in Nice Class 3, and ‘medicine’ and ‘food supplements’ in Nice Class 5. Was this a safe option?

The German company Hecht-Pharma GmbH filed an application for revocation due to non-use.

Gufic Biosciences was initially able to prove that the trade mark appeared as an independent sign on the packaging of its frankincense tablets, both on ‘Sallaki TABLETS’

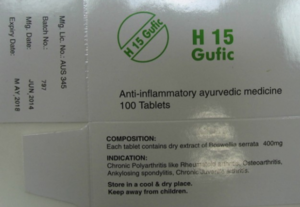

and on ‘H15 Gufic’

The proven sales of the products were also sufficient to establish genuine use.

But were the tablets actually being used for the goods for which they were registered? Gufic Biosciences claimed that its frankincense tablets were medicinal products and that the trade mark was therefore being used for medicine. However, in the European Union, the frankincense tablets had not been approved for use as medicines – this was only the case in India.

Hecht-Pharma claimed that the tablets also lacked the pharmacological effect required in order to be classed as medicines. In addition, in Germany, the unproven benefits of the active ingredient had led to the company being legally prevented from using any medical claims in its marketing. The tablets could not be marketed as any kind of medicines. Hecht-Pharma argued that these factors meant the trade mark could never be used for the category of medicines, and therefore it should be cancelled in relation to this classification.

Were they correct?

The European Medicinal Products Directive 2001/83 (EC) recognises two definitions of medicinal products. Firstly, there are so-called medicinal products by function, i.e. medicinal products that have a significant pharmacological effect on the human body. Secondly, the Directive defines medicinal products as so-called medicinal products by presentation. These products do not have the pharmacological effect that a functional medicinal product does. However, because of their external form and presentation, they give the (false) impression that they are could serve to cure or prevent human disease, like a functional medicinal product. The Directive aims to protect consumers from such products, which is why it classifies them as medicinal products.

But is this distinction in pharmaceutical law relevant to trade mark law?

The objectives of the Medicinal Products Directive are quite different from those of trade mark law. The Directive aims to achieve the free movement of medicinal products within the European Union, taking into account the protection of public health. Trade mark law, on the other hand, is designed to distinguish products according to their commercial origin. The classification of a product under other provisions of Union law is therefore in principle irrelevant for the assessment under trade mark law.

However, it can be stated that, in relation to medicinal products by presentation, both trade mark law and the law on medicinal products are based on the consumer’s perspective. Thus, the likelihood of confusion in trade mark law is assessed from the consumer’s point of view. And medicinal products by presentation are medicinal products only because they are perceived as such by the consumer on the basis of their presentation. Therefore, if a consumer considers a product to be a medicinal product, they will also consider that the trade mark used for it is being used for medicinal products. A medicinal product by presentation is therefore also defined as a medicinal product under trade mark law.

It was therefore only necessary to decide whether consumers would consider the frankincense tablets of Gufic Biosciences to be medicinal products by presentation.

As can be seen above, the packaging was labelled ‘TABLETS’, and it featured the words ‘AYURVEDIC MEDICINE’ and in particular the indications for various inflammatory diseases such as osteoarthritis, myositis and fibrositis. In addition, the products could only be bought from pharmacies with a doctor’s prescription, due to the laws regarding imported unauthorised medicines. All these details of the product’s composition, taken together, gave consumers confidence in the pharmacological efficacy of the tablets that is typical of pharmaceutical products.

Consequently, the Gufic trade mark was also used for medicine within the meaning of trade mark law, and the application for revocation was rejected in this respect. Whether the tablets were functional medicines and had a pharmacological effect, whether their distribution was illegal or not, and whether the frankincense tablets were dubious medicines or not, was irrelevant for trade mark law. The only issue was whether the mark was being used for the registered goods. As shown, this was the case.

Hecht-Pharma has referred the matter to the European Court of Justice. However, it is highly questionable whether the Court will take up the case on the basis of its previous practice.

General Court of the European Union, January 11, 2023, case T-346/21.

Learnings: A badly thought-out list of goods can come back to haunt you. If you want to use a trade mark for food supplements or cosmetics, you should check whether the products could later be regarded as medicinal products. The external form and presentation of the products will determine this. If, in such a case, you do not have trade mark protection for medicinal products, you run the risk of losing your trade mark for this product.