Brand preservation after ceasing production – TESTAROSSA

The case: Brand preservation after ceasing production will present a brand owner with major challenges.

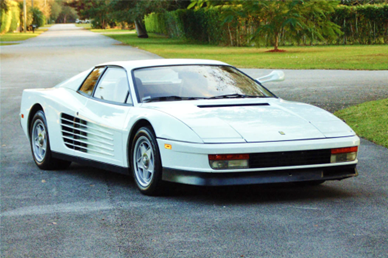

Between 1984 and 1991, Ferrari sold about 7,000 units of a super sports car under the name of

Among other things, the car became world-famous as a police vehicle in the TV series Miami Vice, and as a celebrity vehicle:

TESTAROSSA means ‘red head’ and alludes to the red-painted valve covers of the sports car:

As a trade mark, TESTAROSSA was registered, inter alia, in Germany in 1987 and 1990 for ‘vehicles, in particular automobiles and parts thereof’.

When Kurt Hesse, the Nuremberg toy manufacturer known for his true-to-the-original toy cars, realised that Ferrari had not sold any TESTAROSSA sports cars for more than 20 years, he registered his own brand TESTA ROSSA in 2014. He wanted to use the well-known brand name for bicycles, eBikes and razors.

Ferrari filed an opposition against this trade mark application.

In return, Hesse applied for cancellation of the German TESTAROSSA trade marks on the grounds of non-use. He held that no new car had been sold in the five years before the request for cancellation, and the trade marks were unused and only known because of their history. However, all economic operators must be free to re-use unused trade marks.

Ferrari argued that during the relevant period, it had resold used TESTAROSSA vehicles that had been tested by it. In addition, it offered maintenance, repair, restoration and certification services for the TESTAROSSA model on an ongoing basis. The company also maintains a stock of spare parts and acessories for the vehicles in question. In Germany, approximately 77 spare parts marked with the brand were sold per year, achieving an average annual turnover of €2,800. In addition, a large turnover was not a prerequisite in the niche market in question.

Notwithstanding this, the Düsseldorf Regional Court ordered Ferrari to consent to the cancellation of the challenged marks. The Düsseldorf Upper District Court, however, had some reservations about this decision. It asked the European Court of Justice for guidance on the criteria to be used to assess whether cancellation of the trade marks could be actioned in the present case, given that production had ceased.

In its landmark answer, the Court of Justice first clarified that a trade mark proprietor can use their trade mark not only when distributing new goods for the first time, but also when distributing used goods, and thereby preserve it in law. Even if the goods have already been sold once, the trade mark can indicate the commercial origin of the product when it is distributed again. Contrary to the opinion of the District Court, it is irrelevant in this context that third parties may freely resell trademarked goods that have been put on the market by the trade mark proprietor. This did not have any bearing on the question of use to preserve the right.

Further, the Court pointed out that the use of a trade mark for spare parts and accessories constitutes use of the trade mark for the main goods. Spare parts are part of the composition or structure of the main goods – an integral part of them. Accessories are directly related to the principal goods and satisfy the needs of the purchasers of those very goods. Thus, when such goods are marketed under the trade mark, they are readily associated by consumers with the main goods already marketed: the trade mark is then used for the main goods, albeit only spare parts and accessories are being marketed under the trade mark. The distribution of the spare parts and accessories under the trade mark TESTAROSSA was therefore – subject to further review by the upper district court – a use of the trade mark for the registered motor vehicles. It no longer mattered that Ferrari had also registered its trade mark for the spare parts alongside the car.

The Court also clarified that the same principles apply to Ferrari’s maintenance, repair, restoration and certification services. Indeed, these services are also directly related to the main goods and satisfy the needs of the purchasers of those very goods. If these services were in fact provided under the TESTAROSSA trade mark, which still had to be confirmed by the Upper District Court, this would also constitute use of the trade mark for motor vehicles.

All the acts of use referred to by Ferrari could thus constitute effective use of the TESTAROSSA marks for motor vehicles if the mark was actually used in those acts.

This raised the further question if this use of the trade marks was genuine. Were the proven trade mark uses only symbolic due to the fact their use had been on such a small basis, a situation which would not usually be sufficient to preserve the rights of the trade marks?

The Upper District Court had doubts if this use was genuine because of the limited extent of the acts of use, in relation to the huge reference market of motor vehicles in Germany, the category in which the trade marks were registered.

The Court made it clear that it is the entire market of motor vehicles that must be considered a reference market. The use for a special product or service can only have the effect of preserving the rights of such a generic term, which coherently groups goods or services together on the basis of shared characteristics and purposes. Luxury sports cars, however, do not constitute a definable coherent sub-group in the market for motor vehicles. Like normal motor vehicles, they can be used for the normal transport of passengers and luggage. The fact that they can also be used for car racing does not lead to the designation of a separate product group. Indeed, if a product fulfils several purposes at the same time, it would be arbitrary to refer to only one of those purposes in order to form a coherent group of products. Nor is it relevant to the definition of the product group that the sports cars are luxurious and high-priced and are sold in a ‘special market segment’. This is because these criteria indicate nothing about the specific relevant characteristics and purpose of the cars.

Therefore, what mattered for the preservation of the rights of the TESTAROSSA marks was whether the sales figures, measured against the market for motor vehicles in Germany, were sufficient to retain or gain market share in the market for motor vehicles. If they only indicated token use, they would not be serious enough to preserve the trade marks. As in the Walzertraum decision, a very large reference market was thus decisive here!

Unlike the handmade chocolates in the Walzertraum decision, however, the TESTAROSSA luxury sports cars are extremely high-priced goods that are naturally only sold in small quantities. On this basis, the sales figures achieved did not, in contrast to the opinion of the lower courts, indicate a priori that Ferrari’s use of the trade mark was not genuine, although this was ultimately left to the court’s assessment.

Court of Justice of the European Union, 22 October 2020, C-720/18.

Learnings: If you want to preserve the rights of your registered trade mark after the production of the branded goods has ceased, you should examine whether a distribution of used goods as well as of spare parts, accessories and services directly related to the goods, and satisfying the needs of the buyers of the main goods under the trade mark, can be taken into account. However, the sales thus achieved must be sufficient, measured against the reference market, to maintain or gain market share in that market.