Brand for ordinary product shape – Coca-Cola

The case: Everyone is familiar with the Coca-Cola contour bottle with fluting.

When it was registered as a Union trade mark, it was already almost 100 years old. Consumers immediately recognise it as a Coca-Cola bottle. Consequently, it is protected as a trade mark in the European Union.

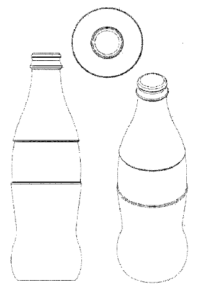

To extend the protection of the bottle shape, Coca-Cola registered a simpler shape as a trade mark. It consisted of the shape of the familiar contour bottle, only without its fluting:

The re-registration, however, failed.

Why?

The General Court of the European Union found that consumers primarily see in a beverage bottle simply a container for a certain quantity of a beverage. The shape of a beverage bottle must therefore already deviate significantly from the norm or what is customary in the industry in order for it to indicate the origin of the beverage as coming from a particular company. The simplified shape of the Coca-Cola bottle, however, consisted only of components which are all common in the beverage sector, including the combination of such components.

However, an ordinary three-dimensional shape, which is not distinctive as such, may also acquire its distinctiveness through use. Consumers may have learned through the use of the product shape over time that the product shape indicates the origin of the product as coming from a certain company.

Coca-Cola submitted surveys carried out in ten major European Union countries as such evidence. The survey’s showed that consumers in these countries saw the bottle shape as a means of identifying the origin of the drink through use over time. However, this was not enough for the court. The evidence had to be provided for the entire European Union, which had not been done. It had not been proven that the other markets in the European Union were comparable to the markets covered by the survey. Moreover, the results between the individual countries varied too much to be extrapolated to all Member States.

However, Coca-Cola also relied on its sales figures and advertising material in the European markets. However, this alone did not prove that the target audience perceives the bottle shape as an indication of the commercial origin of the drinks.

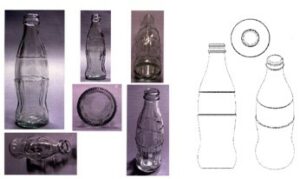

However, perhaps the new shape could benefit from the already registered well-known mark if it could at least be considered as a part of that mark. The shape would then have been co-used with the other mark. And consumers could have come to recognise, in this way, that the new bottle shape was also associated with beverages from Coca-Cola.

Comparing the two bottle shapes as they appear in the trade mark applications,

they are identical except for the grooves. The new form contains all the outlines of the known form. But did this mean the shape was already therefore only a part of what constituted the trade mark? Or did consumers always see the use only as a use of the well-known mark? Ultimately, this could not be clearly decided. The proof of a use of the new sign as part of the well-known mark could not be established because of the great similarity between the two shapes.

The new bottle shape was not registered as a trade mark as a result, General Court of the European Union, 24 February 2016, T-411/14.

Learnings: If you want to monopolise the shape of a product in the European Union for an indefinite period of time by means of a trade mark, it should deviate significantly from the norm or what is customary in the industry. If this is not the case, you must prove, across the entire European Union, that the public has learned to attribute the shape of the product to a particular company. Make all the necessary preparations for this in good time so as not to incur wasted costs.

For a protectable bottle shape that was applied for as a trade mark by Coca-Cola on the same day, see the article Bottle shape as a brand – Coca Cola in this blog.