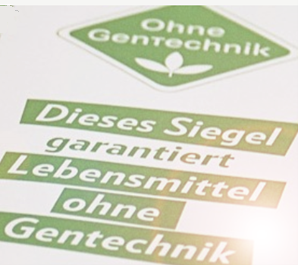

Deception from GM label? – Without genetic engineering

The case: In 2009 the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture developed a dedicated GM label [‘GMO-free’] for the benefit of consumers:

It is intended to distinguish genetically unmodified products from those containing genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

For this kind of seal, a certification mark is the appropriate instrument for trademark protection. It is intended to distinguish goods with certified properties from goods that are not certified. In the present case, this means certified genetically unmodified products as opposed to those that are not certified, with the certification mark promising independent certification. The exact specifications of the properties to be certified and the conditions of use are laid down in regulations governing use of the mark. These regulations are published in the trademark register together with the trademark, for everyone to see.

The ‘Verband Lebensmittel ohne Gentechnik e.V.’ (VLOG) [Association for Food without Genetic Engineering] was granted the rights to use the genetic engineering seal, having applied for the registration of the GM label as a certification mark for food and animal feed, among other things. On its website, the association advertises that the seal guarantees that food displaying the seal has not been genetically engineered:

While the regulation under which VLOG submitted the application governing the use of the seal requires the food to be free from genetically modified organisms, it does allow for certain exceptions. The label may still be used, for example, if the food or its ingredients contain technically unavoidable or adventitious traces of genetically modified organisms. This is tolerated up to a determination limit of 0.1% per ingredient, i.e., up to 1 gram of genetically modified organisms per kilogram of ingredient.

Cattle, for example, need only to have received no GM feed for 12 months before slaughter and three-quarters of their lives. For small ruminants, such as sheep, the tolerance period ends six months before slaughter. For pigs, the period is four months, and for dairy animals, a period of three months before milk production. For poultry, if intended for meat production, the period is ten weeks if the animals were taken to a stable within their first three days of life, and if kept for egg production, they only have to be fed GM-free food during the six weeks before egg production.

On this basis, the EUIPO refused to register the certification mark. A certification mark must not deceive the consumer, which was considered could be the case here. The trademark promised freedom from genetic engineering but could not keep this promise.

VLOG countered this. It referred to the fact that such food items were in full compliance with the statutes with the European rules, as well as the stricter regulations of German law. Moreover, food production is complex and multi-layered. Individual steps regularly have to be taken over by third parties. It is not reasonable to have to ensure without any restriction that the final product supplied has been produced to be 100% GMO-free. It argued, in addition, that consumers are very well informed about food and expect minimal contamination.

However, the EUIPO did not accept this reasoning. The general German public, at whom the trademark was aimed, would not be aware of such exceptions and would therefore be guided by the wording of the trademark. As a rule, the fewer potential linguistic differentiations, the more likely it is that the public will understand a certified property in its literal sense.

This was not a criticism of the exceptions from a health perspective. The EUIPO also stressed it was understandable that it is not possible to avoid a small proportion of genetically engineered material.

However, there was no room for interpretation of the wording ‘Ohne Gentechnik’ [without genetic engineering]. In addition, the graphic elements of the seal had no restrictive effect; they merely supported the word elements.

The situation was different from that of beer, for example where, a distinction is usually made between alcohol-free beer (with alcohol residues) and ‘beer without alcohol’ or ‘0.0%’. A certification mark, however, which promises – without any room for interpretation – that the labelled products are GMO-free, poses a risk that consumers might be deceived, as this is not always the case.

It was irrelevant that European and German laws allow exceptions to the freedom from genetic engineering. If this were relevant, the certification mark would lose its meaning. It is supposed to ensure for the consumer that products can be distinguished according to their certified properties. However, if it unambiguously refers to the certification of certain properties, which – according to the regulations governing its use – do not always have to be present, its very purpose is called into question.

Thus, because the government seal has the potential to deceive the consumer, it was denied the protection of a certification mark. It now remains to be seen whether the Court of Justice of the European Union will take up the case.

EUIPO, Second Board of Appeal, 5 May 2023, R 2229/2022-2

Learnings: Brands must deliver what they promise. To this end, it is advisable to closely analyse the words and graphic elements of such marks. A certification mark will not be protected if its deceptiveness is apparent from its wording and the regulations governing its use, as in the present case. An individual mark will not be protected if there is no way in which it can be used without deception. However, irrespective of the question of the protectability of such marks, misleading use of deceptive marks is always prohibited. It is therefore better to counteract the risk of deception as early on as the sign’s design stage!